What is the best way to build a good rapport between owners, the board of directors and the CEO?

“At that point, I had to carefully consider whether I could continue.”

Tom von Weymarn reflects on the year 2006, when the board of directors of an international telecommunications group was in the middle of heated discussions. As chairman of the board at the time, von Weymarn was the one leading the debate.

In addition to being a professional board member, he now works as a consultant and coach in the field of corporate governance.

“Then, I was handed over a dissident board from the onset”, von Weymarn recollects.

Ideally a board as well as it’s chairman should have enjoyed amicable, confidential relations with the company’s Chief Executive Officer. This, however, was not the case.

“We had reached a point where trust in the CEO was beginning to run out. Some had a particularly critical attitude, while others were pre- pared to show support primarily for power reasons”, explains von Weymarn.

The board was dissatisfied with the company’s results. The president was also under scrutiny for doubtful judgement on a number of issues as well as limited processes related to many emerging markets. The disparity culminated in a harsh exchange of words between some members of the board and the CEO.

“After several rounds of discussions and faced with a big enough issue representing very doubtful judgement by the CEO, I finally announced that if the board could not agree on the dismissal of the CEO even under these circumstances, I together with a couple of additional board members would resign.”

This sort of an approach is not an everyday occurrence, as lack of confidence usually results in the resignation of the CEO rather than the chairman and board members.

The board appoints and dismisses the CEO, not the other way round.

The exception to the rule resulted in an equally exceptional response: the owners stepped in.

“The company’s main owners were not particularly happy with the way things were turning out”, states von Weymarn.

They decided to hold an extraordinary general meeting where approximately 50 per cent of the board members were changed. The extraordinary general meeting also decided to ask von Weymarn to continue as chairman of the board, as proposed by the nomination committee.

Shortly after the next annual general meeting the CEO was dismissed by the new board in order to “improve the atmosphere”, as stated in the company’s press release.

***

This episode illustrates how difficult managing a company can get, when the three top layers are out of sync.

In principle, a clear hierarchy prevails among owners, the board of directors and the managing director, whereby the board exercises the power of the owners and monitors operational management. Reality is of course a great deal more complicated than a simple organisation chart.

Established on legislation and corporate governance, the rules of the game are only the starting point. What happens on the playing field de- pends on the players – the chairman of the board and managing director in particular.

To up the challenge, seamless teamwork between these players is key to a company’s success.

But how to create a functional relationship between a company’s board and operational management? And how does a board of directors that is up with the times and under- stands its own role actually function? What should be expected of a man- aging director appointed and trusted by the board? This article examines corporate governance and its underlying rules through the eyes of four experts in the field.

Tom von Weymarn speaks from experience. With a background in corporate governance, he has also served as the CEO for a number of different companies. In addition von Weymarn has been a member of the board in up to 30 different companies, usually as the chairman of the board.

“Exercising power is embedded in strong individual human behaviour”, says Tom von Weymarn.

“It all de- pends on the individual and personal characteristics. An intention to use power is ingrained in the role of a managing director. Without this characteristic, a managing director fails. A managing director needs to be as strong-willed as possible, but balanced by an equally strong-willed board.”

Board professional Marina Vahtola currently holds the position of Executive in Residence at Aalto University School of Business, and is a board member in several companies, as well as a senior adviser for international chains based in Sweden and Germany. Before her current role, Vahtola worked for over a decade as CEO of a number of different companies.

“Trust is the key word”, states Vahtola.

“In addition to competence and experience, trust is a vital factor in successful business. True appreciation and trust enable building growth and reacting to changes surrounding business. If trust is missing, we often talk about chemistry between people. As is the case in one’s personal life, in the end trust can crumble simply due to emotional reasons. After all, we are all human.”

Jesper Lau Hansen, Professor of Company Law and Financial Market Law at the University of Copenhagen, has particularly examined the Nordic corporate governance model. He is more than familiar with the type of drama in the boardroom described by von Weymarn and Vahtola.

“Nordic governance is extremely honest, marked by a culture of discourse and informality. Addressing in first person and heated debates may even come as a culture shock to others”, says Hansen. “In the Nordic countries, board work is a rather strange mix of fierce disputes and consensus. Those unwilling to seek unanimity are shown the door.”

Our fourth interviewee is Professor of International Economics and Management Steen Thomsen, who is the executive director and founder of the Center of Corporate Governance at the Copenhagen Business School.

“The relationship between a company’s board and managing director is a rather unknown entity. It is a challenging field of study, as the subject matter is so intricate – a bit like examining particles”, says Thomsen. “But team leadership can be explored in general. Hardworking leaders who motivate their team members usually reap results. It probably comes as no surprise that an enthusiastic coach – or chairman of the board in this case – ends up succeeding.”

***

According to Jesper Lau Hansen, the Nordic corporate governance model is based on the Danish Public Companies Act of 1930.

According to the Act, large enterprises must have someone in charge of day-to-day management in addition to a board of directors. Thus, the Act refers to a managing director and defines two layers; the board of directors and managing director. This model continues to be the foundation for corporate law also in the other Nordic countries.

The picture becomes a bit more blurred when examining who actually occupy these layers.

Firstly, the managing director may have a dual role: in Sweden, 40 per cent of managing directors are also members of the board of the company they run. This is a common occurrence also in Finland despite a somewhat lower percentage.

Secondly, an owner may be both a board member and involved in operational management.

“The same person filling several different seats is common especially in the case of family businesses”, mentions Tom von Weymarn.

“This easily leads to situations of jealousy and owners tugging in different directions.”

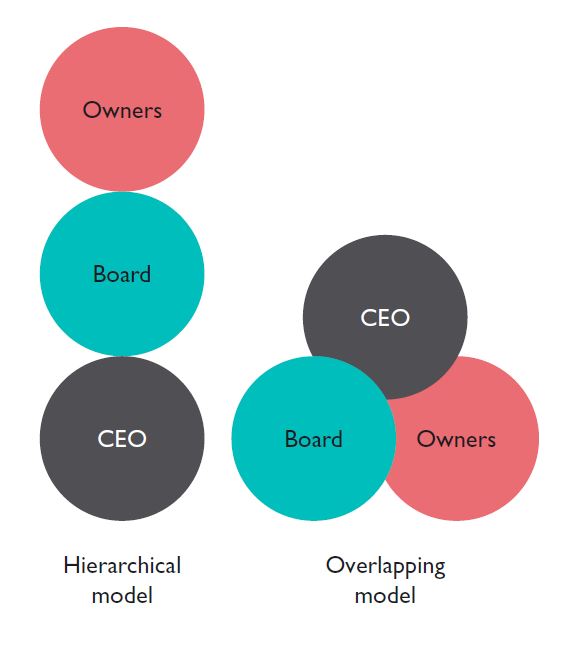

Listed companies usually operate according to a clear-cut hierarchical model, with owners, the board of directors and management placed on top of each other.

Often roles and power relations overlap a great deal in smaller risk investment companies. Regardless of what the organisation chart may state, a similar, so-called integrated model is prevalent also in larger companies in the Nordic countries especially in practical operations.

A managing director influences the board’s decision-making, while the board has an impact on operational decisions - all usually in good spirits. Striving for consensus is another typical feature of Nordic corporate culture, the decision- making process culminating in unanimity.

“In Germany it is stated separately that board members, i.e. ‘advisers’, may not be part of the company’s executive management. This is explained by the fact that boards in Germany can include as many as 15 members”, Hansen states.

In situations where owners have differing views concerning the company’s revenue requirements or strategy, the board of directors may be in a serious state of internal conflict. In many cases co- owning siblings fall out with each other, or a state owner has a very different concept of running a company compared to a private owner. While owners and their representatives on the board are busy arguing, managing directors may end up with more power than intended.

Yet legislation makes it seem clear that the owners and the board that represents the owners dictate what goes on in a company. In principle, the board decides on a long-term strategy and ensures that it is implemented by the managing director in day-to-day operations. But yet again what really happens is another story; the managing director usually exercises a great deal more power than is formally prescribed.

The interviewed corporate governance experts emphasize the role of the managing director. A company’s strategy is not wisdom that trickles down from the board to the CEO – quite the contrary. Grasping the strategy is teamwork that involves the board requesting the managing director on a continuous basis to update the company’s future plan.

The managing director processes the strategy with his or her subordinates, i.e. the management team, before presenting strategic options as well as the recommended approach to the board of directors.

“The strategic process is owned by operational management and usually requires in-depth discussions by the management team”, says Tom von Weymarn. This is quite natural, as involvement in daily operations gives the managing director a clearer understanding of the ins and outs of the company compared to the more distant board.

In today’s chaotic business environment any company must have both a learning operational top team as well as a fast-learning board of directors. The pre-requisite for such dynamics is a genuine and transparent dialogue involving top management and board – and pretty much on a continuous basis.

“If decisions of the board are repeatedly in conflict with the managing director’s proposals, the situation begins to get under the managing director’s skin. The managing director becomes careful and unwilling to take risks.”

Managing directors must not be crushed, but they do need challenging.

“In the Nordic countries, challenging and coaching the managing director is a key task of the board”, Jesper Lau Hansen explains.

Marina Vahtola accentuates this further.

“The board needs to make demands on the managing director. This doesn’t necessarily mean being demanding in a negative sense”, she says.

“There must be respect towards each other’s expertise, but also a trust that management knows what it’s doing. To a degree, one must give space, but naturally the board also has responsibilities and its members are responsible for their decisions. The board needs to demand any relevant information from the managing director.”

Vahtola notes that the main focus of the board should always be on the long-term strategy and future of the company.

“Successful business demands continuous development. Composing the company’s strategy together with the management team and overseeing the development process are the board’s key responsibilities.”

***

While boards have become more professional, pressures on the managing director have also increased.

Managing directors have increasingly shorter terms of office; according to an estimate, on average managing directors now hold the same position for only four years. In the after- math of the financial crisis, a managing director is in for a particularly shaky ride.

“Managing directors need to realize that the risk of getting fired has increased”, says Steen Thomsen, Executive Director of the Center of Corporate Governance at Copenhagen Business School.

“Today, CEOs work harder and are under more stress than before. It is likely that their creativity and out-of-the-box thinking are in danger of receiving a hit at the same time.”

When talking about confidence in managing directors, Thomsen mentions sympathy. The board needs to be able imagine itself in the managing director’s heavy boots.

“Building trust is closely linked to familiarity and transparency. The chairman of the board and the managing director need to have a rapport and some degree of sympathy. Even if it is missing on the outset, sympathy can be built over the course of time”, says Thomsen.

“Without sympathy everything is harder.”

How close can the chairman of the board and the managing director actually be?

“Like mentor and mentee?” poses Thomsen. “Perhaps a little more distant, as we’re talking about a coach, who can change the team around.”

Trust and sympathy do require a degree of closeness. Marina Vahtola reminisces on what it was like to be a managing director without a close rapport with the board:

“The support of the board is vital for the man- aging director. I was the CEO for an international company for a long time with a very distant board. I came to see that the further away the board seemed, the harder communication be- came. Often numerical meters amplify in international companies – only because of the geographical distances. There’s less communication and more pressure to meet numerical goals.”

The equation is near impossible: a managing director wishes for support, coaching and close communication, while also needing space, trust and a certain amount of independence.

A board wants the managing director to provide vision and implement the board’s decisions.

“Being close buddies with the chairman of the board isn’t enough”, reminds von Weymarn.“The managing director needs to be trusted by the entire board.”

***

But what happens when the confidential relationship between the board and managing director takes a blow at times?

The board needs a plan B. Even if teamwork is smooth, owners and the board need to be ready for the possibility of a new captain in charge. The board selecting the managing director and the managing director appointing other managers used to be enough. Now the board needs to also be acquainted with the company’s management team that comes under the managing director. The board needs to know who will be managing the company in the event the managing director leaves or is dismissed. On the other hand, it is fairly common for the chairman of the board to step in as interim managing director in situations of crisis.

“In the end, the board doesn’t have that many roles. The main tasks are to appoint and oversee the managing director – dismissal is a great deal harder”, says von Weymarn.

As a golden rule, the first year is usually when the managing director is frowned upon in the event of problems. Issues are discussed during the second year. If problems persist during the third year, the managing di- rector is asked to leave.

The situation appears rather merci- less from the managing director’s perspective. The managing director may have been hired for a crisis company, where steering the strategy and processes require tough decisions, years of hard work and perhaps persistence with many years of bad results.

“Problems can be lived with also during the third year, if the company isn’t in a worse state than its competitors or if a sacrifice has been made that won’t reap rewards until later on”, estimates Thomsen.

Sometimes there is a dip even during better times. Not all investments have immediate returns.

“There may be challenges, when a managing director wants to develop something new or suggests embarking into new markets. These are the moments where trust is measured”, describes Marina Vahtola.

“It often takes some time before new ventures take off or things are settled on a new market. Without trust, proposing these types of issues to the board can be risky. The board should have sufficient understanding and competence to take in the proposals of the managing director. If this is not the case, the CEO can hardly get the support needed. Sufficient competence in the board se- cures the development of the company. This is why the composition of the board should also be re- viewed regularly.”

Verbalising reasons for trust and its loss can be difficult, as it is a question of emotions. Once again, everything boils down to two elements: the chairman of the board and the managing director.

“Their relationship is crucial”, says Vahtola, who has experience from both roles.

“The relationship needs to be confidential, smooth and demonstrate mutual respect.”

A rift between the chairman of the board and managing director can jeopardize the position of the other board members. Owners are rarely interested in or able to address internal power struggles. The situation described by von Weymarn at the beginning of this article of a chairman being ready to step aside in a situation of conflict is by far the more unusual turn of events.

“These days it is common for a managing di- rector to transfer to another role merely for reasons of personal chemistry, when a relationship doesn’t work”, says Vahtola.

Reasons vary, both in the public statements and behind the closed doors. Let’s look at some examples.

Antti Pankakoski, managing director of Finnish state-owned manufacturer of alcoholic beverages Altia, was dismissed in December 2013. Also his predecessor Leena Saarinen was forced to step down. Reasons can be manifold, but the phenomenon does illustrate the dilemma of state owner- ship: profits need to be made, while Finns should be drinking less.

Timo Kohtamäki, ex-CEO of Finnish construction company Lemminkäinen, was dismissed in April 2014. According to Berndt Brunow, Chairman of the Board of Directors at Lemminkäinen, the dismissal is explained by dwindling profit performance, yet it roused suspicion in the industry.

“There’s no other reason. Of course speculation arises when a good person has to leave”, explained Brunow in Finnish newspaper Helsingin Sanomat. “The board of directors decided on his dis- missal. Naturally, weak profit performance played a part. The board is of the opinion that the company’s agility needs to be accelerated.”

The chairman of the board became the interim CEO of the company owned by the Pentti family. Kohtamäki headed the company for approximately five years. He was hired to renew and improve the company’s profit performance.

As demoralizing, vague and emotional as it can get a managing director’s faltering position is jus- tified. The main job of the board of directors is to protect the owners’ interests, and at best a demanding, strict board can spread an atmosphere of fairness further afield.

Allowed too much freedom, managing directors have created a great deal of trouble.

“The entire financial crisis is a result of this”, says von Weymarn.

***

It is indeed a valid argument that one reason for the global crisis boils down to irresponsible and greedy managing directors in the financial industry with oil in the wheels but left too much to their own devices.

“Overseeing the managing director is the issue at hand”, von Weymarn says. “I’d couple this with keeping the managing director’s ego in check Self-esteem is an important element, as a company’s success is so closely tied with the ability of the managing director and his or her team to make it rain.”

“It is the board’s task to support, but also to make sure the ego doesn’t grow out of proportion. An over-sized ego creates the worst damage. The risks get to high.”

In the peak years before the financial crisis, a large proportion of international financial giants became slack with financial analysis. With money pouring in, managing directors and boards were too caught up in the flow to pause and analyse the situation. Managing directors who begin to think that rules no longer apply to them is another tell- tale sign of an overgrown ego. It is all very human, but a dangerous scenario for companies. The phenomenon is usually coupled with a so-called moral hazard resulting from managing directors exclusively operating with external funds.

Of course managing directors are not solely to blame for overstepping the mark, as often also owners and the board of directors have lost their grip. After all, how else could operational management be free to play as they wish.

The way managing directors are compensated for their work and re- warded for exceptional performance provides an efficient supervision tool, keeping their egos under reign at the same time. Hansen and Thomsen agree that strict restrictions must apply to rewarding practices.

A popular method for engaging a CEO in a company is through ownership. However, ownership should be earned by managing directors rather than something that falls straight into their arms.

“This is a problematic area. Compensation and engagement methods vary. A bill was drafted in Denmark in 1940 that would have made it compulsory for managing directors to own part of the company. The draft bill was sidelined, as World War II began”, Hansen explains.

According to Hansen, a director’s salary should constitute the main income paid by the company, while incentives should be made available only if the company does better than its rivals.

“Usually the grounds for incentives are to loose; they are paid for doing as well as other companies in the field”, Hansen criticizes. In Hansen’s view, incentives should be low compared to the main salary.

“Those who do their job well don’t get fired. It’s important to send out a message that we’re already paying you for doing your job well.This should be the basic assumption”, notes Hansen.

Thomsen agrees.

“I’m all for expanding ownership to include the managing director and other executives. However, ownership needs to be earned rather than given away. Managing directors should have to spend enough of their own net income to acquire ownership, so that it actually matters to them. This is a good test of how much a managing director actually believes in the company – a classic way for an agent to reveal his genuine view on a client”, explains Thomsen.

Some companies are quite happy to publicise the managing director’s salary, while others refrain.

According to Hansen, publicity is a double-edged sword. On the one hand, a company may receive positive publicity for paying out generous compensations and attracting the best talent. On the other hand, this can set off a wage spiral that backfires on the company itself.

“Shareholder power is the best wage control, as remuneration comes straight out of the shareholders’ pockets”, Hansen says. This is the reason why companies with a single or a handful of owners rarely pay out huge salaries: for a large owner, salaries constitute a concrete investment rather than a rushed decision by the AGM.

“Managing directors that are so-called fat cats with extremely high salaries are more common in companies with decentralized ownership”, says Hansen.

Remuneration paid to managing directors al- ways gets out of hand during an economic upturn.

“The financial crisis demonstrated that several banks had generous incentives in place also low down in the organization. Stricter practices now apply to so-called high-net-worth individuals. For instance, some banks require the board to sign each agreement”, explains Thomsen.

Yes, the financial crisis.

Recovery efforts have had an impact on corporate governance throughout the industrial world.

Corporate governance rules have become stricter in Britain by increasingly holding company management – i.e. boards of directors – to account. Large-scale institutional investors have been persuaded to take on increasingly responsible and pro- active roles. The underlying idea is for larger owners to have more of a say in companies than so far.

“In Britain, corporate scandals have mainly focused on companies with decentralized ownership. Without a single major owner, no-one is interested in thoroughly supervising the managing director and company operations”, says Jesper Lau Hansen.

“Directors should not be inde- pendent in relation to owners, but accountable.”

In 2010 – a couple of years into the credit crunch – the British Financial Reporting Council published its Stewardship Code for institutional investors. The code encourages large-scale investors to engage in increasingly active ownership, transparency and collaboration with other owners.

The Stewardship Code states: ”For investors, stewardship is more than just voting. Activities may include monitoring and engaging with com- panies on matters such as strategy, performance, risk, capital structure, and corporate governance, including culture and remuneration. Engagement is purposeful dialogue with companies on these matters as well as on issues that are the immediate subject of votes at general meetings.”

As engaged ownership of this type comes with a price tag, institutions have begun to employ proxy agents. This doesn’t remove the problem but in essence externalises shareholder responsibility.

The new British code seems to resemble Nordic corporate governance, does it not?

“It is an attempt to turn institutional investors into responsible owners. In my view it doesn’t work”, announces Hansen. According to Hansen, the problem is that an institutional investor may own a slice of a company, yet from the perspective of the institution – be it a pension fund, insurance company or an investment fund – the ownership still constitutes a small investment.

The Government Pension Fund of Norway, coined by the public as “the oil fund”, is a good example. The fund has indicated that it would be implementing an increasingly proactive ownership policy in companies of which it has a share of over 5 per cent. As a result, a representative of the fund is now a member of the board of directors of Swedish truck company Volvo. However, a 5 per cent ownership of Volvo is like a needle in the haystack for the Norwegian pension fund, which owns approximately one per cent of all of the world’s shares.

Studies also show that large institutional investors have not succeeded particularly well in their investor engagement, whereas hedge funds have managed to influence companies and reap major rewards.

With its headquarters in London, global security services company G4S Secure Solutions made a bid to acquire major Danish cleaning company ISS. The merge would have resulted in the world’s biggest company offering security and cleaning services. However, directors at G4S failed to convince owners, with especially certain activist funds campaigning against the deal. The share price of G4S fell amid suspicions over the merge, and hedge funds managed to sweep up a sufficient amount of the cheaper shares to prevent the deal.

Finally, G4S was forced to cancel its offer in late 2011, the share price rose and the hedge funds made a huge profit.

During a new, more open but equally volatile era, boards may be facing tougher times. They need to be able to justify their decisions to share- holders. Otherwise the outcome may be revolt, as illustrated by the story of G4S.

***

So how can a company be protected from conflict?

Despite good intentions, active ownership does not always work. Operational management that is too free and strong may head down a risky road. On the other hand, a board that breathes down the managing director’s neck is not optimal either. “Things run smoothly and best results are reaped with expertise and competence sitting at the same table”, states Marina Vahtola.

The idea may sound simple, but comes as some- thing of a relief among all the differences of opinion and power struggles. Companies have the potential to succeed provided that each position is filled with the right skillset, and subsequently all of the elements respect each other’s expertise.

If approaching corporate governance from a conventional point of view, this may seem like a challenge; boardrooms are no longer filled by who you know, but require the right expertise and experience.

“Board members can be required to have in- depth knowledge. Boardrooms need individuals with their own areas of specialisation coupled with an ability to see the big picture. They need to have a thorough understanding of the decisions they are making”, says Vahtola.

“An inadequate board doesn’t understand the point. It doesn’t recognize what is vital and ur- gent”, describes Tom von Weymarn.

“On the other hand, if a board has a great deal of sector-specific expertise, a board member may end up being a real pain in the neck to the man- aging director. Someone might start challenging the managing director over something pointless. It all ends up in a struggle over who wins.”

Boards of directors increasingly work in committees, members forming sub-divisions to pre pare decisions and focus on particular areas. Any developments that make corporate governance more professional are welcome. Yet care must to be taken that the board does not step on the toes of operational management.

“The place of a board of directors is not on the shop floor”,Vahtola points out.

The number of board professionals has risen in recent years, and the circles are no longer so small. According to a study conducted last year by a Danish headhunter company, the average age of board members had decreased considerably. New talent and an increasing number of women have entered the boardroom.

A case in point is the way headhunters have replaced nomination committees in seeking new board members.

Although the final decision of a board’s composition lies with the biggest owners, competition is so fierce that they need assistance in finding the best resources. According to Jesper Lau Hansen, a typical board these days has just 3-5 members, meaning there is no room for choosing the wrong candidate.

In the Nordic countries, women still rarely occupy board seats of listed companies. Hansen points out that one should not stare at the figure of women making up half of the population when considering their low representation in company boards. “A typical board member is an executive of some other company. More women will join the ranks, as more women become CEOs, CFOs etc. Now women have reached a level just below the managing director. If there’s a glass roof somewhere, that’s where it’s at.”

“Boards have clearly become more committed and professional over the last decade”, clarifies Steen Thomsen.

This has partly been spurred by the financial crisis. “The competence of board members has been emphasized a great deal during the crisis – before, independence was the buzzword”, Thomsen compares.

Regulators emphasize the importance of expertise and competence especially in financial companies. This has resulted in an increasing share of boards being made up of both sector-specific and financial experts.

The board of directors of Denmark’s biggest company Mærsk, known for its container shipping services, is a prime example of this phenomenon. Mærsk typifies Nordic companies in the way it has a single strong owner – the Mærsk family – that controls the company through foundations.

Five of the 12-member board can be described to be top financial experts. Ane Mærsk-McKinney serves as vice-chairman of the Mærsk Group’s board of directors. Her son Robert Mærsk Uggla, who is in his thirties and has a degree in economics, was appointed as a member of the board in April 2014. Chairman of the board Michael Pram Rasmussen is also an adviser for the International Council of investment bank JPMorgan Chase; member of the board Sir John Bond is the former chairman of HSBC, one of the world’s largest banks; Arne Karlsson is the former president of Swedish Ratos private equity conglomerate; and Dorothee Blessing is the former co-head of German investment bank Goldman Sachs.

“Boards are keen to find members who master accounting and finance”, summarizes Thomsen.

The members and tasks of boards have become more professional. According to Steen Thomsen, the same applies to their remuneration.

“Board members used to always be paid an even, moderate fee. These days they still receive a basic fee, but are also expected to acquire shares in the company. In my opinion, board members should invest their remuneration in the company’s shares and retain the shares until some time after they’ve left”, says Thomsen.

Board members would have to prove they believe in the company by becoming shareholders. The same should be the case for the managing director.

It is interesting that although the boards of Nordic companies are becoming increasingly international, studies have shown that multicultural boards are not necessarily reflected in improved results. As a point of comparison, companies in the US with boards comprising solely US-citizens are more successful on the market than equivalent companies with international boards of directors.

In other words, let’s pick the best experts on the market in order to provide owners with the best possible agents for overseeing their assets. We need to make sure that in addition to their own area of specialisation, experts have the ability to see the bigger picture.

Teams should be chaired by individuals with emotional intelligence, who understand their responsibility as the managing director’s counterpart and coach – even listener.

In appointing a managing director, we need to look for someone who is honest, has the right amount of hunger and makes things happen. A “rainmaker”, as experts often say.

A strategy should be drawn up jointly based on the managing director’s sector-specific competence, but understood and shared by the members of the board. Everyone should commit to the joint plan. “The more views differ, the more time, energy and cigarettes are wasted on meaningless arguments”, Tom von Weymarn sums up.

In the end, the rules of the game are simple.

“Sandpit psychology”, says von Weymarn. “That’s what it’s mainly about. Power is always in the hands of the one with the strongest, most personified strategic intent.”